Early Career Scientist Spotlight

Mr. Isiah Holt (he/him/his)

Astronomer

X-ray Astrophysics Laboratory (662)

Did you always know that you wanted to study astronomy?

Not directly. Science was an interest to me when I was in middle school, but astronomy was not at the forefront. As I started taking more science classes in high school, I also started to think about what subjects I’d be cool to learn more about. I wasn’t in the mindset of wondering “what am I going to major in college?” until I reached my junior year. When I took physics in junior year, I started to consider it for my college major. Still, I quickly learned how difficult it would be to study physics, and it was so broad in material that the thought of majoring in physics was a bit overwhelming. Astronomy came along as an optional General Education class later in the year, and I enrolled in the course, loved it, and the rest was history. My senior year project was centered on becoming an astrophysicist and that project prepared me for my college journey of studying astronomy at Penn State.

Credit: Charles Hapich

What science questions do you investigate?

I am investigating possible systematic uncertainties and biases on estimates of neutron star radii. Neutron star radius measurements are very valuable because having a precise and reliable radius estimate can provide you with the necessary information to learn about the very dense matter in the star’s core. For this reason, many studies have estimated neutron star radii using X-ray observations. It has become evident that many of these estimates, which have typically been based on the fluxes, spectra, and distances, are potentially susceptible to significant systematic errors. In particular, fits to the data can be statistically good and the inferred radii can be precise, and yet the radius estimates can be substantially biased. However, recent data from the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) mission adds a new component to this data: each photon can be timed to better than 100 nanoseconds, which is so much shorter than the rotation periods of neutron stars that it is possible to see the spectrum change as the star rotates, rather than just the average spectrum. Early studies suggested that with this extra depth of information, systematic errors are not problematic: if there is a statistically good fit, then the inferred radius is reliable.

The goal of my thesis work is to elaborate substantially on these early studies of possible systematic errors using a sophisticated range of tools that have been developed in the process of analyzing NICER data. These tools fit the data under the assumption that the X-ray emission from the surface of a non-accreting pulsar can be described by a set of “hot spots”. The hot spots are thought to arise from particles being accelerated on the star's magnetic field lines and slamming into its surface, heating it, and emitting X-rays. We consider different configurations of spots, as well as different possible stellar masses, radii, and so on, and one of the results of our statistical analysis is a measurement of the radius of the star.

My work will explore systematic errors by generating multiple synthetic data sets from different model waveforms and analyzing their fit quality. Initially, I will build intuition by working with one-spot models. However, given that the NICER data thus far have required at least two spots, I will then transition to the much more computationally intensive study of two- and possibly three-spot models.

Credit: Charles Hapich

How did you end up working at NASA Goddard?

When I first started my Ph.D. at the University of Maryland, I told many people that working at NASA was a goal of mine. In my second year of graduate school, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center opened the Pathways Internship Program for sciences, and my advisor, Dr. Cole Miller, and my mentors, Dr. Kartik Sheth, Dr. Brad Cenko, and Dr. Stuart Vogel, all encouraged me to apply. I applied to the program, and when I received an offer from the Astrophysics Division, I was ecstatic. I was so shocked that what I thought was only a dream had actually come true right before me. I will never forget all the support I received from advisors, mentors, family, and friends as I worked to achieve this.

Tell us about one project of yours that has been particularly impactful in your early career.

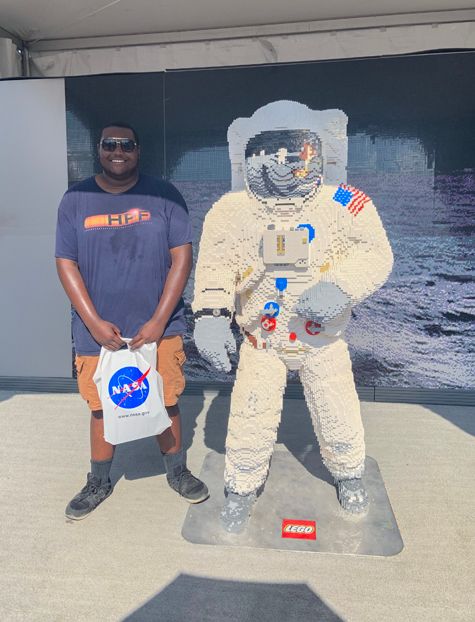

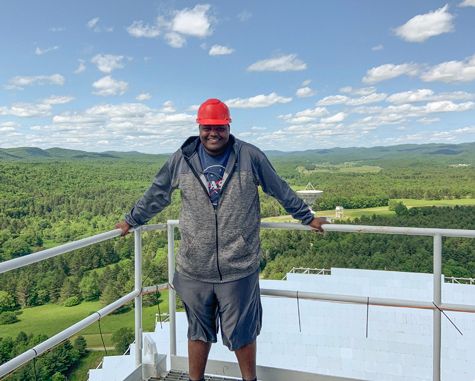

In the summer of 2019, I was accepted into the Physicists Inspiring the Next Generation program at the Green Bank Observatory to study fast radio bursts (FRBs). An FRB is a radio flash with high flux density and millisecond duration which typically appears to happen once for an object and never repeats. Recent work challenges this idea, suggesting that most FRBs will repeat at some point in their lifetime, and some, such as FRB 121102, have been reported to repeat many times. Because of this, and the possibility of localizing the bursts through repeat detections, we decided to investigate another FRB with similar properties, FRB 110523. Unfortunately, after thorough analysis over 40 hours of observation data using the PulsaR Exploration and Search Toolkit (PRESTO), I determined that there were no additional bursts during the observation. However, even given the ultimate failure of the search (something that I learned in frontier research), I better understood the research process and enjoyed investigating FRBs' mysterious features.

Credit: Max Hawkins

Tell us about a moment in your career that you are particularly proud of.

I jumped into research at Penn State in my first year by joining the Pulsar Search Collaboratory (PSC), where I learned what pulsars are and how to detect them. I got certified to search for pulsars in the PSC citizen science database. This first exposure to research motivated me to look into getting a research position in the department as soon as possible. I attended an astronomy club lecture by Dr. Jason Wright about exoplanets and was so intrigued that, after the talk, I went up (despite being really anxious initially) and asked if I could work with him. He told me to come back once I had learned a programming language. Inspired by this, I took a course on Python in my second year. Dr. Wright accepted me into his group, where I worked on Python projects related to the instrument NN-explore Exoplanet Investigations with Doppler spectroscopy (NEID). I started to become more confident in myself ever since that club meeting, and I’ve always thought of that as a big accomplishment for myself.

Credit: Ell Bogat

What do you like to do in your free time?

I like to try new recipes in the kitchen during my free time. I have watched many cooking shows (MasterChef, Diners Drive-Ins and Dines, Iron Chef, The Final Table, etc.) that have inspired me to change up some of the recipes I typically make. A good bit of them end up a disaster, but some recipes turn out nice and are in my rotation when I decide to cook.

I am a huge gamer when I have the time. PlayStation and Nintendo have been my go-to consoles for years. My favorite games are fighters such as Tekken, Street Fighter, and The Naruto Shippuden Ninja Storm Series, and 1-player adventure games such as Resident Evil, Legend of Zelda, and Pokémon.

When I get the chance, I also practice Japanese flashcards so I can start learning the language. I am currently using Anki Flashcards and trying to immerse myself in the language through other types of media. In the future, I hope to hold short conversations with a buddy to better grasp pronunciation and communication skills.

Credit: Isiah Holt

What aspects of your career do you enjoy the most?

A favorite aspect of my career is being involved in mentorship programs. While I was at the Green Bank Observatory, I mentored rising high school students, helping them with their research projects using the 40-foot educational telescope on-site. I learned a lot through that experience by listening to the student's thoughts and questions about astronomy and sharing my excitement about the field.

Another favorite aspect of my career is learning to think deeper about research questions and develop greater intuition. One of my goals as I work through graduate school is to gain experience asking the types of science questions that lead to new research projects in the future.

Credit: Cecilia Chirenti

Biography

Home Town:

West Mifflin, PA

Undergraduate Degree:

B.S. Astronomy & Astrophysics and B.S. Physics, Penn State, University Park, PA

Post-graduate Degrees:

PhD Astronomy (in progress), University of Maryland, College Park, MD